Academic Hall Fire-Columbia-January 9, 1892 |

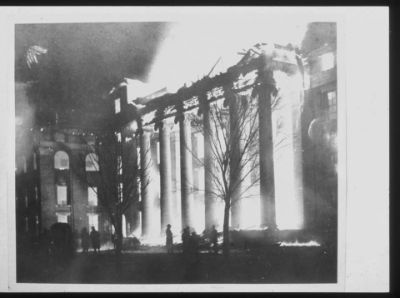

Shortly after 7:00 p.m. on January 9, 1892, the Athenaeum Literary Society was preparing for an entertainment session inside the chapel of Academic Hall on the campus of the University of Missouri- Columbia when a small fire was observed near the ceiling. Students, staff members, and volunteer fire fighters began directing hose streams onto the fire; however, the water supply in the basement cistern was soon exhausted, having had little effect on the blaze.

The flames consumed Academic Hall by midnight. The cause of the fire was rumored to be wires being used to power the first electric light bulb west of the Mississippi River.

While the fire destroyed the structure, it left the six iconic columns at the center of the Francis Quadrangle, which we all cherish today.

Board of Curators President G.F. Rothwell famously proclaimed "let these columns stand. Let them stand a thousand years". |

|

In the wake of the Academic Hall fire, there was a significant effort in the Missouri General Assembly to relocate the University to Sedalia. The City of Columbia approved infrastructure spending to improve water supply and fire protection to the campus. The private volunteer group, Columbia Fire Company, would eventually become the Columbia Fire Department and hire their first paid staff in April 1901. |

American Tent and Awning-St. Louis-February 3, 1902 |

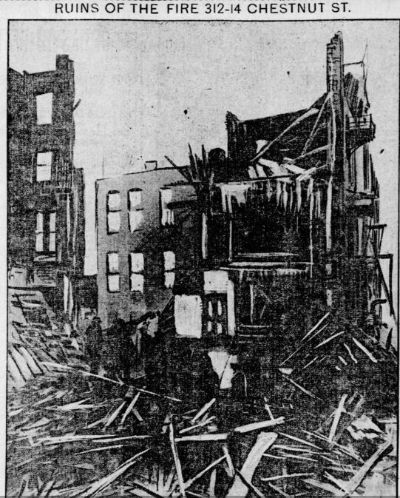

On February 3, 1902, at approximately 8:00 p.m., the St. Louis Fire Department responded to a structure fire at 312-314 Chestnut Street, the American Tent and Awning Company. Initial arriving units reported fire on the fourth and fifth floors of the nearly fifty year old building, on what was reported as the coldest night so far of the 1901-02 winter season.

Approximately one hour after the fire was reported, and with the flames mostly under control, crews were sent to the upper floors to extinguish remaining spot fires. Without warning, the structure collapsed. Afterwards, Fire Chief Charles Swingley was quoted as saying "to all appearances, there was no danger to the pipemen who went into the upper floors, the fire was all on the fourth and fifth floors, and more on the fifth than on the fourth. Under such conditions no one would expect a building to collapse". It was later revealed the structure had been seriously damaged by a May 1899 fire. A contractor had been hired by the owner to install "an additional row of girders" to repair the damage.

Without the benefit of modern technical rescue equipment readily available today, nearly all of the debris removal and rescue was done by hand. The sounds of survivors still trapped in the rubble ceased at 1:00 a.m. and the first firefighter was not freed from the debris until 3:00 a.m., but died en route to the hospital.

Seven St. Louis Fire Department members were killed, the largest loss of life in a single event in the department's history.

|

|

|

Great St. Louis Fire-May 17, 1849 |

On Thursday, May 17, 1849, the City of St. Louis was in the midst of a cholera epidemic which would ultimately kill over 4,000 residents. A steamboat from New Orleans named the White Cloud was moored on the north end of what is now Laclede's Landing, when a mattress fire was reported in one of her cabins. The fire was extinguished on the deck of the boat, and the mattress placed it back in the cabin.

At approximately 10:00 p.m., volunteer fire fighters from the Missouri Fire Company Number 5 were summoned and arrived on-scene to find heavy flames visible from the deck of the White Cloud which had already extended to another steamboat, the Edward Bates. The flames caused the Bates to break free of its moorings and float downriver, spreading the fire to other boats moored along the landing. Strong winds helped the flames quickly overwhelm the fire crews; within 30 minutes, 23 steamboats were engulfed in flames along the riverfront of what is today the Gateway Arch grounds.

|

|

Embers from the rapidly developing firestorm rained down onto cargo at the landing, shanties, and structures along Front, Locust, and Vine Streets. Simultaneously, another fire south of Market Street caused by the blazing steamboats, consumed many wood-frame homes. Bucket brigades and weak fire streams proved no match for the growing inferno and caused residents and fire crews to retreat to safer ground. A few all-brick structures were spared by the flames. The old cathedral block at the intersection of Walnut Street and Third Street was spared when fire fighters created a fire break by blowing up buildings on Market Street with "explosive powder."

During the process of creating the fire break, a premature explosion at the intersection of Second Street and Market Street killed Captain Thomas Targee, who became a hero of the St. Louis Fire Department, established in 1857. Fire fighters continued to save downtown buildings by kicking embers off of rooftops.

By the time the fire was brought under control on May 18, 1849, 418 structures spread across 15 blocks had been destroyed. Three people were confirmed killed in the fire; however, it is believed more lives were lost. |

| HA HA Tonka Castle-Camdenton-October 21, 1942 |

On October 21, 1942, sparks from a chimney ignited the roof of a large, limestone castle which had been constructed between 1905 and 1922 on a 250-foot high bluff overlooking a small, spring-fed lake, outside of what is now Camdenton. The lake would later be consumed by the creation of Lake of the Ozarks. Construction of the castle, the vision of Kansas City businessman Robert Snyder, began in 1905; however, was stopped when Mr. Snyder was killed in 1906, the victim of one of the first automobile accidents in Missouri. After a period of time, Snyder's sons resumed construction, and the less elaborate structure was finished in 1922. The mansion had 28 rooms and featured a center atrium, rising 3 1⁄2 stories to a skylight, a private water tower, and carriage house. Mr. Snyder initially envisioned a 60-room European-style castle with multiple greenhouses and stables.

In the 1920s and 1930s, the castle served as a weekend and summer home for the Snyder family. The property was eventually converted to a hotel. The 1942 fire destroyed the castle and carriage house, and in 1976, the original water tower was destroyed by a fire intentionally set by vandals. The water tower was later restored.

|

|

In 1978, the castle ruins and surrounding property were purchased by the State of Missouri and Ha Ha Tonka State Park was created. In 2015, USA Today named Ha Ha Tonka fourth in the "Best State Park in America" category, selected from 20 nominations from across the United States. Today, the park welcomes over 500,000 visitors annually, who come to experience the karst topography, natural bridge, sink basin, natural spring, hiking trails, and castle ruins. |

| Hyatt Regency Skywalk Collapse-Kansas City-July 17, 1981 |

On July 17, 1981, approximately 2,000 people were attending a "Tea Dance" at the Hyatt Regency Hotel in Kansas City. Tea Dances had become a popular Friday evening event for the city in the summer of 1981. The Hyatt Regency, located in the Crown Center complex near Union Station, was the tallest building in Missouri at the time and featured an elegant lobby with suspended skywalks on the second, third, and fourth floors spanning the atrium.

At approximately 7:05 p.m., with the crowd swing dancing to the song "Satin Doll", the skywalks on the second and fourth floors suddenly collapsed onto the crowded dance floor below. Fire crews from across the metro area descended on the lobby to begin rescue efforts. On arrival, they discovered many victims trapped beneath tons of concrete, steel and glass. Working without the aid of modern technical rescue equipment, on-scene commanders put out an urgent call for help from local construction companies and equipment suppliers. These unsung heroes brought concrete saws, torches, compressors, jackhammers, and heavy-lift jacks to assist in freeing victims trapped beneath the rubble. Cranes were brought to the scene and the booms forced through the atrium glass to help lift the debris off of trapped victims. During the collapse event, fire sprinkler pipes were severed, causing a torrent of water to fall onto the atrium floor; the rising water additionally threatened the lives of trapped victims. Much of the 14-hour rescue effort took place in the dark since building power was disconnected to reduce the chance of fire during the rescue effort.

114 lives were lost and approximately 200 injured. A subsequent investigation conducted by the National Bureau of Standards cited structural overload resulting from design flaws as the cause of the accident.

The Hyatt Regency Skywalk disaster would remain the deadliest structural collapse in the United States, until the collapse of the World Trade Center South Tower on September 11, 2001 and remains the deadliest non-deliberate structural failure in U.S. history.

|

|

| |

| Katie Jane Memorial Home-Warrenton-February 17, 1957 |

On February 17, 1957, at approximately 2:30 p.m., a 92-year-old resident at the Katie Jane Memorial Home in Warrenton thought he smelled smoke on the first floor of the sixty year old annex building; however, no one heeded his warning. Approximately 10 minutes later, a visitor in the hallway observed flames coming from the linen closet beneath the stairwell leading to the second floor. Bed-confined residents were housed on the second floor so that ambulatory residents would not be required to transit stairways.

It took an estimated five minutes for the visitor to locate an employee, the employee to verify the presence of fire, reach the telephone located in the office of the main building, and phone in the alarm. During this time, the fire rapidly spread through the annex making reentry impossible. The Sunday afternoon weather was unseasonably warm leading residents to have their windows open; this allowed smoke and fire to quickly sweep through the open passageways into the main building and throughout both structures.

|

|

Initial responding units from the Warrenton Volunteer Fire Department arrived at 3:08 p.m. to find the facility fully engulfed in flames. Witnesses reported the smoke column was visible for 30 miles.

72 residents were killed in the blaze, many in their bed and locked in their room. This fire remains the deadliest nursing home fire in U.S. history.

Key factors contributing to the severity of this fire were open stairwells, lack of an automatic sprinkler system or fire alarm system, lack of staff training or evacuation plan, no smoke barriers, and no enclosed interior exits. This facility was found to have been operating without a license. |

| Second State Capitol Building-Jefferson City-February 5, 1911 |

On February 5, 1911, Jefferson City residents were enjoying an unseasonably warm Sunday afternoon when a thunderstorm rolled through the capitol city at approximately 6:15 p.m. Monsignor Joseph Selinger was in the area of St. Mary's Hospital when he witnessed a bolt of lightning strike the dome of the Missouri State Capitol building. A short time later, some boys playing in front of the building noticed smoke coming from the dome. The current from the strike had traveled down old electrical wires in the dome and ignited the structure's pine frame. Flames were soon visible from the windowed structure at the top of the dome called a lantern.

Hampered by low water pressure and a lack of ladders able to reach the raging flames in the dome, Jefferson City's volunteer fire companies were quickly overwhelmed. Initial calls for assistance were made to the state penitentiary, where trustees were freed to help battle the flames. An urgent appeal was sent out to surrounding communities for assistance. At 9:55 p.m. a special train was sent from Sedalia containing fire apparatus and manpower, which remarkably made the 64-mile journey in 77 minutes, a record at that time.

|

|

Realizing the battle to save the state house was lost, the focus quickly shifted to a salvage operation in an effort to save the precious documents, paintings, and artifacts housed inside. Secretary of State Cornelius Roach formed a human chain, hundreds of volunteers long, to save items from the burning structure. Many documents, paintings, and state records were saved as a result including original land grants and the 1865 resolution ending slavery in Missouri. Many of these documents are housed today in the Missouri State Archives and the Missouri State Historical Society, charred around the edges from the flames that night.

While a significant number of priceless pieces of art and other items were saved, some were lost, including George Caleb Bingham's portraits of Thomas Jefferson and Henry Clay.

The flames burned for most of the night, with the glow visible for 20 miles, completely consuming Missouri's second capitol building. At 4:00 a.m., a water main break in the Mill Bottom area halted the work of the firefighters.

During the process of funding a new capitol building in the wake of the fire, there were several attempts to move the capitol city to the St. Louis area, Sedalia, or West Plains. It took several years to replace the destroyed structure with the current capitol, on the same site, which was completed in 1917. |

| Southwest Blvd. Fire-Kansas City-August 18, 1959 |

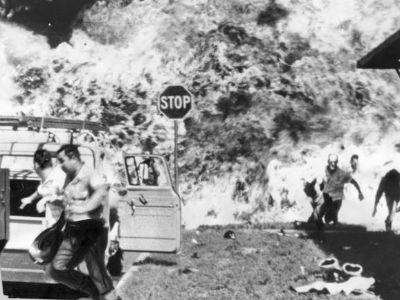

On August 18, 1959, at approximately 8:20 a.m., the Kansas City Kansas Fire Department responded to a flammable liquid fire at the Continental Oil Company, 2 Southwest Blvd. The facility was a combination service station and bulk storage plant near the Kansas-Missouri state line. Initial arriving units reported heavy smoke and fire showing from the facility. Leaking gasoline had extended underneath four 11x30 cylindrical horizontal storage tanks resting above ground, each with a 21,000 gallon capacity.

At 8:33 a.m. a first alarm mutual aid assignment was requested from the Kansas City Missouri Fire Department. As the fire spread, additional KCFD alarms were requested in rapid succession, a second alarm at 8:37 a.m., third alarm at 8:45 a.m., fourth alarm at 8:54 a.m., and fifth alarm at 8:59 a.m. High August temperatures combined with a 13 mph wind, high humidity, and the radiant heat of the burning fuel, hampered the efforts of fire crews. Firefighting foam technology was in its infancy in 1959 and although a foam apparatus was on- scene, it was ineffective because there was no way to control and contain the leaking gasoline to create a foam blanket.

|

|

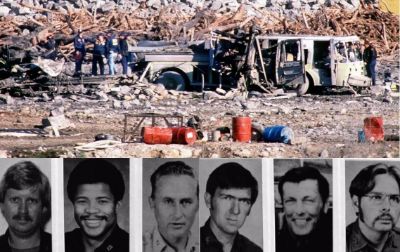

Tanks 1, 2, and 3 failed; however, they did not leave their concrete cradles. At 10:00 a.m., Tank 4 failed, rocketing 94 feet onto Southwest Blvd., traveling through a 13-inch brick wall, and spreading bricks and burning gasoline along its path, engulfing fire fighters and equipment. Witnesses described the sound of Tank 4's failure as a "roar like a jet engine". The failure of Tank 4 destroyed two pumpers, damaged three others, and killed five KCFD Fire Fighters. A sixth alarm was requested from KCFD after the failure of Tank 4. By 11:00 a.m., the inferno was brought under control.

The cause of failure of the four tanks was determined to be inadequate venting, resulting in over-pressurization when exposed to fire conditions. Because of this tragedy, National Fire Protection Association codes were changed to require bulk flammable liquid storage tanks be placed underground. Fire fighter training also saw changes resulting from this disaster. New procedures were developed to fight fires involving horizontal storage tanks, emphasizing approach of the tanks from the sides instead of the ends. Fire Officers stressed the importance of wearing full bunker gear during firefighting operations as many of the fire fighters injured in this fire were not wearing their gear.

The concept of mutual aid played a key role in this fire and became more common across the country as a result. |

| Ammonium Nitrate Explosion-Kansas City-November 29, 1988 |

On November 29, 1988, at approximately 3:40 a.m., the Kansas City Fire Department responded to a vehicle fire at a construction site along U.S. Highway 71 near 87 th Street. During the 911 call, a security guard in the background could be heard saying "the explosives are on fire." Pumper 41 was assigned to the alarm. Dispatchers cautioned Pumper 41 of the potential for explosives at the scene.

At 3:46 a.m., Pumper 41 arrived on-scene and found two separate fires burning and requested an additional pumper be dispatched to assist. Pumper 30 was assigned and arrived on-scene at 3:52 a.m. Discovering multiple fires at the scene, the Incident Commander suspected intentionally set fires and requested law enforcement officers respond to the scene. At approximately 3:57 a.m., Pumper 30 requested a Battalion Chief be dispatched "emergency" to assist. Over the next several minutes, it became clear there was confusion as to if there were actually any explosives on site, or if any were involved in the fires. At 4:02 a.m., a truck, trailer, and large industrial compressor were burning. There is no indication that any of the vehicles, or trailer were marked, indicating the presence of explosives, as markings were not required by the ATF or DOT at that time.

|

|

Unknown to the crews of Pumper 41 and 30, the trailer that was burning was actually an explosives storage magazine. At 4:04 a.m., Pumper 41 contacted the Battalion Chief stating that "he's got magnesium or something burning up here." The Battalion Chief and driver were just arriving on-scene and staged approximately ¼ mile from the scene. At 4:08 a.m., 22 minutes after the arrival of Pumper 41, and 16 minutes after the arrival of Pumper 30, the magazine exploded, killing six Kansas City fire fighters. The Battalion Chief and his driver both suffered minor injuries when the windshield of their staff vehicle was blown in. Approximately 40 minutes after the first explosion, a second explosion occurred with several additional, smaller explosions.

The crater from the initial blast measured 80 feet in diameter and eight feet deep, the crater from the second blast measured 100 feet in diameter and eight feet deep. The subsequent investigation revealed the first explosion involved 20,500 pounds of ammonium nitrate/fuel oil mixture. The second magazine trailer contained 1,000 30-pound containers of ammonium nitrate/fuel oil mixture.

In 1989, the Kansas City Council passed an ordinance adopting the NFPA-704 marking system. The Kansas City Fire Department also implemented new policies requiring notification of blasting material and projects within its jurisdiction. The Occupational Safety and Health Administration adopted regulations requiring all hazardous material transportation containers to maintain appropriate DOT placarding and labels when used as fixed storage.

Also in 1989, the Kansas City Fire Department Hazardous Materials Team was established. The numbers 41 and 30 (Pumper 41 and Pumper 30) were merged to form Hazmat 71 in honor of the crews lost in this incident. |

| Gasonade County Train Wreck - November 1, 1855 |

On November 1, 1855, at approximately 9:00 a.m., during a prolonged period of heavy rain, a passenger train carrying approximately 600 dignitaries and invited guests departed St. Louis Seventh Street Station (near today's Busch Stadium) with great fanfare, festivities, and speeches, bound for Jefferson City. The 15-car-train was being led by the locomotive "Missouri". The purpose of this trip was to travel the recently completed 125-mile section of track linking St. Louis to the state Capitol, and meet with Governor Sterling Price to celebrate the construction milestone and promote further westward construction of the rail line. However, the new rail line was not fully completed. The trestle spanning the Gasconade River near the town of Gasconade, was still under construction and the track was supported by a temporary structure.

As the train approached the rain-swollen Gasconade River crossing, the plan called for the train to stop and allow the dignitaries to view the 760 foot trestle and for Chief Engineer Thomas O'Sullivan to inspect the trestle prior to crossing. Due to time constraints, it was decided not to stop the train because another train with "heavy gravel cars" had used the trestle the day before and a single locomotive had crossed the trestle as a final check, just prior to the excursion train's arrival, both without incident. At approximately 1:30 p.m., the excursion train approached the trestle. As the train began to cross the trestle, the span between the east bank and first pier collapsed. The steam engine and seven cars fell approximately 36 feet onto the riverbed. The steam engine rotated and landed on the first passenger car, which carried many of the dignitaries, trapping and killing many of those passengers.

|

|

Without modern communication technology, it would take hours before news of the unfolding disaster reached the outside world. The Conductor attempted to send a telegraph requesting help; but the storm had disabled the telegraph lines. Survivors walked from the accident site to Hermann, approximately seven miles, to seek help. Word of the disaster did not reach St. Louis until approximately 8:00 p.m., when the news was relayed by a steamboat. Relief trains were immediately assembled to assist the survivors, but they were delayed by the flooding rains which placed additional trestles in danger of collapse along the route. Before the days of organized fire departments, those trapped in the wreckage had to be freed using basic hand tools and bare hands. Before the storm was over, additional bridges at Boeuf Creek, the Moreau River, and Loose Creek failed due to flash flooding. The initial casualty toll was listed as 31 killed, and 136 injured; however, these numbers were later increased to 43 killed and 200 injured. True casualty numbers are unknown.

Subsequent investigations determined the cause of the accident to be excessive speed and trestle design flaws. Investigators determined the trestle should have withstood the crossing at a maximum speed of 4 mph. The engineer testified his speed was 5 mph entering the trestle; however, witnesses estimated the train's speed at 15-30 mph. This accident remains the worst railroad accident in Missouri history and was the first fatal rail bridge collapse in the United States. In 2002, construction workers for Union Pacific Railroad were digging in the area of the accident and discovered a wheel forged in 1854 believed to be from an accident car. |

| Coates House Fire - January 28, 1978 |

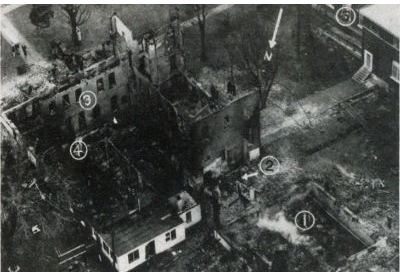

On January 28, 1978, at approximately 4:10 a.m., the Kansas City Fire Department responded to a structure fire in the historic Coates House Hotel at the intersection of 10th Street and Broadway. Initial arriving units reported heavy smoke and fire showing from the six story U- shaped apartment building with multiple occupants trapped inside. The 92-year-old structure was being occupied by transients during this time period.

Single-digit temperatures caused Ice buildup, disabling aerial ladders, and causing hand line nozzles to freeze, significantly hampering the efforts of fire crews. KCFD stuck a 5th alarm, bringing 23 apparatus and 90 fire fighters to the scene, the largest KCFD response to a single event at that time.

It took approximately four hours to bring the flames under control. The fire resulted in 20 fatalities, the deadliest in Kansas City history; however, 150 residents were saved by the heroic efforts of KCFD crews. |

|

| Two key factors contributing to the severity of this fire were open stairwells and a non- functioning fire alarm system. Significant changes came to Kansas City in the wake of the fire including stricter fire code enforcement-specifically fire alarm systems, an emphasis on public fire prevention activities, and fire fighter training. |

|